On Sept. 8, the first day of class for Baltimore County Public Schools, there were no exuberant students waiting for the school bus, no principals and teachers welcoming students to class, and no BCPS superintendent and school board members making the rounds visiting selected schools.

Instead, because of the pandemic, students began the new school year receiving their math, language arts and other instruction, virtually, at home. They are connecting with their teachers online using school-issued Chromebooks, tablets and other devices, and doing so from dining rooms, home offices and bedrooms repurposed as classroom space.

The 2019-20 academic year was cut short this spring when the state superintendent closed Maryland public schools on March 26, and Baltimore County and other jurisdictions moved to a “continuity of learning.” Some say their students lost academic focus and rigor during that period without the structure.

Now, parents say, they are working through a more structured fall semester, where students, depending on their grade level, are receiving between two and 3.5 hours of instruction. Students are to return to the school house on Jan. 29, but BCPS decisions on the timeline keep changing.

Adjusting to a New Routine

After a challenging transition in the spring, Tanesha Sparrow says she, her husband and two daughters, Raya, 9, and Taylyn, 18, are adjusting to the new normal with a workable routine. She welcomed the school system’s decision not to return students to in-person classes. “I was worried about sending Raya back to school. If they opened schools back up, I decided I’m going to home-school her,” says Sparrow.

A fourth grader at Milbrook Elementary School, Raya has learning space is in the dining room, close to where her mother does work remotely as a Department of Energy contractor. A tri-fold display board, dry-erase board, hooks for her ear phones and other supplies are at her fingertips. Raya is using her own iPad that’s connected to a keyboard, instead of a school-issued device. To connect with teachers and other students, she logs in to BPCS One, Schoology and Google Meet.

In the first week of classes, Sparrow grades the school system’s efforts a B. “You can tell they put a lot more in the virtual learning for the fall. I love the way they’ve put everything together. She has gym—they get up and exercise, she has music. They’re more prepared. It’s working out.”

In addition to the hard work of teachers and principal at Millbrook Elementary, Sparrow also appreciates the help from her older daughter, a graduate of Woodlawn High School, when she is not focused on her own studies. Taylyn is taking virtual classes at Community College of Baltimore for business and works part-time at a senior living complex.

BCPS’s virtual learning set up also has special family bonding benefits. We can have lunch together on Wednesdays, when is individual learning time for students. Also, Raya has no summer cold, sniffles or even allergies since being away from other students.

As businesses and restaurants open and expand their hours, and the timeline for reopening schools evolve, Sparrow says she’s hoping politics trump students’ safety. “If the students are going back in person, they need to show me that my child is going to be safe,” she insists.

In reviewing the past several months, Sparrow’s advice to parents: “Keep an open mind and have patience. The same way [virtual learning] is new for you, it is new for the kids.”

‘It’s Been a Challenge. It’s Different.’

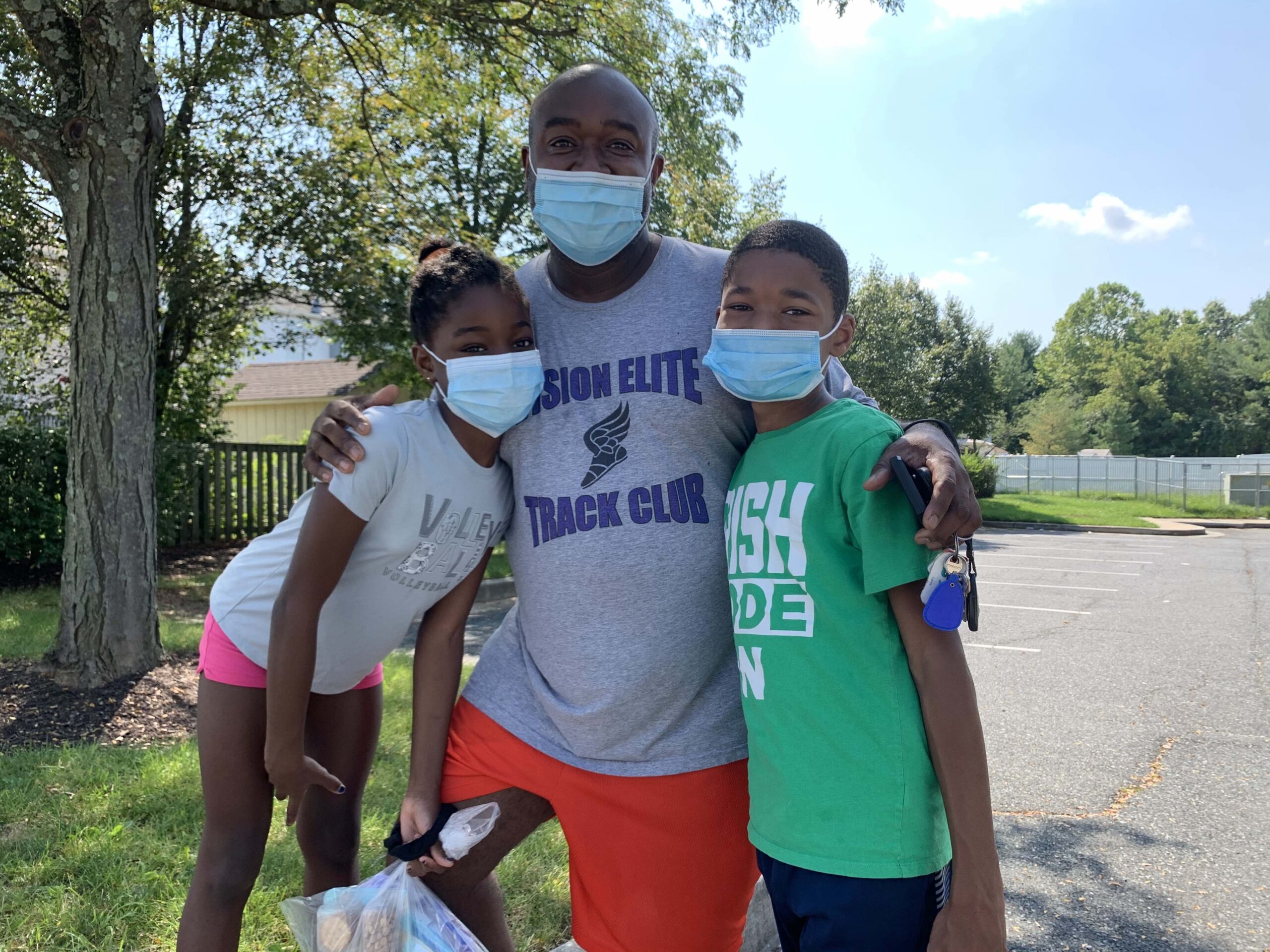

Windsor Mill resident Derek Toney says the new school year is an adjustment for his family “now that the curriculum is more structured and rigorous.”

Since his wife, a Howard County teacher, must focus on her students during the day, he is helping their children Blaire, a third-grader at Dogwood Elementary School, and Taylor, a seventh-grader at Windsor Mill Middle, with their work. Fortunately, Toney says, his work hours are flexible.

“People used to say school is like babysitting. We’re now finding out differently,” he acknowledges.

“I think I was pretty good in math, but this new math has blown my mind,” Toney says. “It’s been a challenge, it’s different. But on the flip side. We as a family have bonded during this pandemic because we’ve been together in the house —minus a week-long vacation—for eight months.”

The lack of social interaction his children are getting is a concern. “If everything works out, when they go back in January, it will be close to a year without being in a brick and mortar building,” Toney says. “You want them to have recess [with other students], have lunch together and have those relationships. They look at us as mom and dad and not as teachers.”

Timeline Evolves

Days before the opening, Superintendent Dr. Darryl Williams released a statement that in response to the announcement from Gov. Larry Hogan and State Superintendent Karen Salmon authorizing school systems to provide in-person instruction, BCPS would look to “incorporate already created hybrid models that include a phased-in plan for small groups of students to return to our buildings.” Teachers and staff were told they’d have to return in October, but that decision has since change. Williams said staff will continue to evaluate the implementation and add groups of students until all have returned to school.

For those concerned about students who don’t log in, chief academic officer Mary McComas told board members, “Attendance and engagement is monitored at the individual school level “Just like in a brick and mortar building, schools are prepared to intervene.”