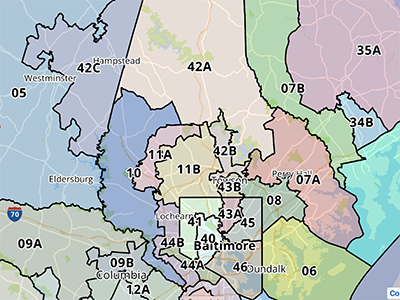

We now know the boundaries of representation for Maryland’s eight United States congressional, 47 state legislative and seven councilmanic districts. After several months of uncertainty, debate and legal challenges to the once-a-decade practice called redistricting, the dust has settled. All maps affecting Marylanders have been finalized after intervention from the courts.

Maryland’s Gubernatorial Primary Election will be held on July 19 (it was originally June 28) and the General Election will take place Nov. 8, the Court of Appeals affirmed. The deadline for candidates, originally extended to March 22 and was finally set at April 15.

As a result of the approved redrawing of the lines, which takes place after the U.S. Census count is released in order to accommodate shifts in population, candidates knew in what districts they could run for office, and launch their campaigns in earnest.

With a lot riding on the outcome of the redistricting process, the original map proposals for the councilmanic, congressional and legislative districts were all appealed by various private citizens, elected officials and organizations on the basis that the maps either were unfair to Black voters, amounted to political or racial gerrymandering or did not comply with requirements of the Constitution.

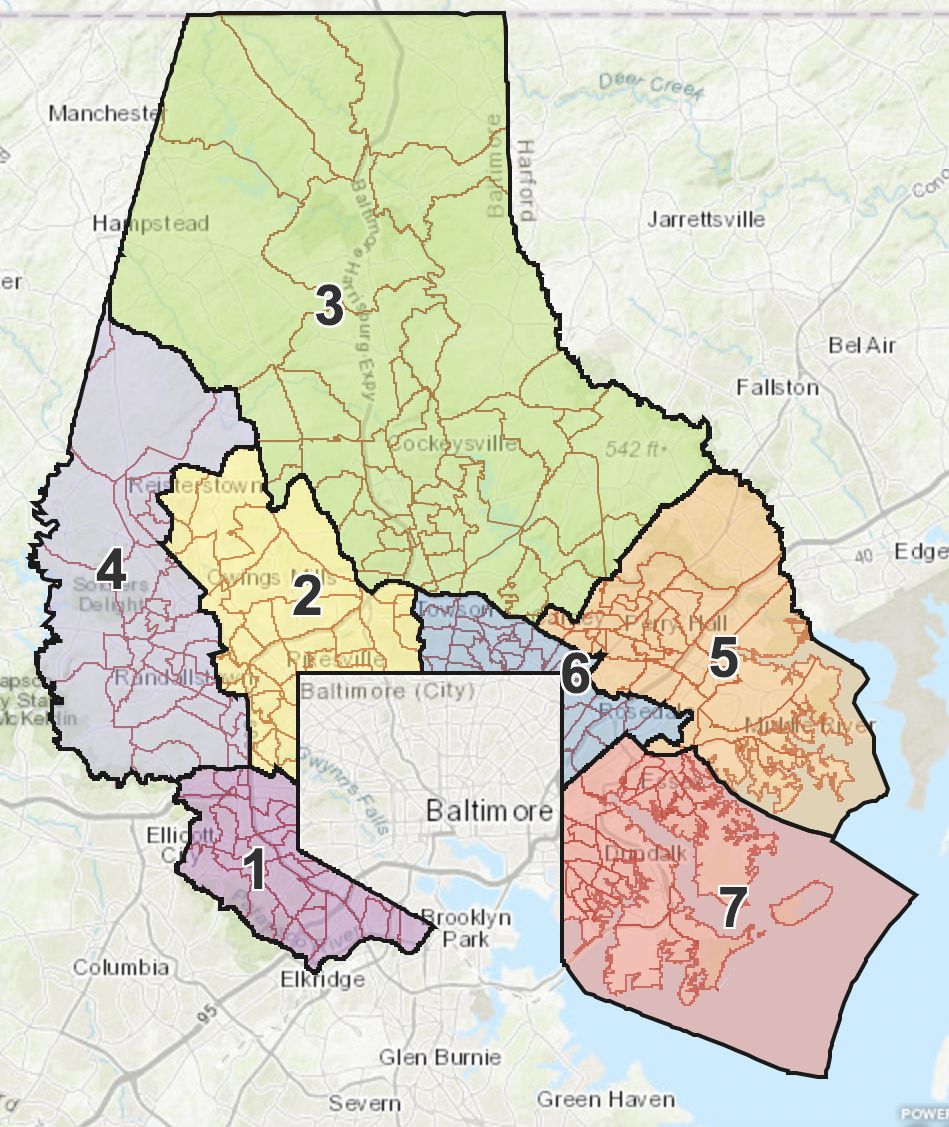

In the case of Baltimore County Branch of the NAACP, et al., vs. Baltimore County, Maryland, the civil rights organization, League of Women Voters of Baltimore and Common Cause – Maryland, and seven Black voters filed a federal lawsuit on grounds the map the County Council adopted last fall violated the Voter Rights Act. Plaintiffs charged that the map reflected cracking and packing a super-majority of voters into certain districts along racial lines.

U.S. District Judge Lydia Griggsby rejected the map Baltimore County submitted last fall and ordered the county to come up by March 8 with a redistricting map that either includes two reasonably compact majority-Black Districts for the election of county councilmembers, or an additional county district in which Black voters otherwise have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice and that comports with the requirements of the Voting Rights Act.

The new map, submitted minutes before the deadline without input from the plaintiffs, was redrawn to include a higher percentage of Blacks in Pikesville-Owings Mills-Lochearn area District 2 (29% to 41%), and reduce Randallstown-Owings Mills-Woodlawn area District 4 from 73% to 61%. District 1 retains its 49.4% white plurality in its voting age population.

In its filing, the county argued that “… the proposed new District 2 contained in the County Map would be “a stronger crossover district,” as well as a coalition district, and that the County Map “also removes any threat of a white bloc voting that may defeat Black voters’ candidates of choice.”

Plaintiffs objected to the county map and wanted the preliminary injunction kept in place. They argued, among other things, that the county map does not provide Black county voters with a meaningful opportunity to elect candidates of their choice. They proposed an alternative map that would reconfigure District 2 to have a Black voting population of 53%, and also for District 4 to have one of 53%.

In the end, the judge approved the county’s revised map on March 25.

The state legislative maps were challenged by a group of Republicans represented by Judicial Watch, a conservative group, and Fair Maps Maryland, an anti-gerrymandering organization with ties to Gov. Larry Hogan. The lawsuits were combined, and in the end, approved. Significant changes to the districts that impact western Baltimore County were left intact.

The state legislature also oversees the congressional redistricting, and Republicans challenged that map, especially taking issue with how competitive the only district represented by a Republican became.

Maryland Judge Lynne Battaglia ordered state legislators to adjust the congressional map, which she referred to as a “product of extreme partisan gerrymandering.” In the end, all parties decided to move forward. Attorney General Brian Frosh, on behalf of the state, dropped his appeal of the judge’s decision. Legislators created a new map, which the Senate and House approved, and the Governor signed.