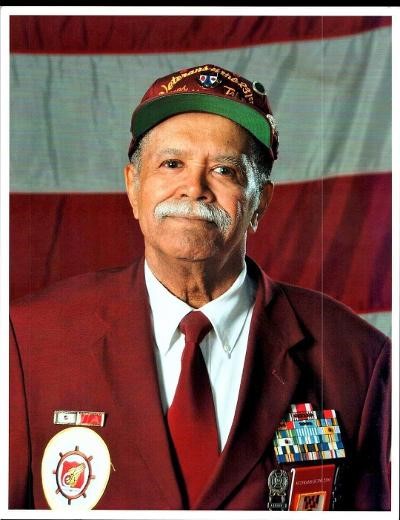

If you had a question about blacks in the military, historic African American churches or settlements in Baltimore County, Louis Diggs, author of 13 books telling the stories about the African American experience, was your source of truth. Since passing away on Oct. 24, 2022, at age 90 in Gwynn Oak, Diggs continues to be remembered for legacy as organizations, churches and families recognize Black History Month.

Distinguished with a warm statesman demeanor, aviator-shaped eyeglasses and thick mustache, Diggs could be found digging through documents at the public library, viewing historic markers around the county, or in attendance at any number of programs and events, often dressed handsomely in a sweater vest or suit and tie.

Born on April 13, 1932, in Baltimore City, Diggs settled in Catonsville in the 1950s. He published his first book, “It All Started on Winters Lane,” in 1995 after retiring from the military and from the Washington, D.C., civil service—each after 20 years. The book chronicled life after the Civil War of families who lived in Catonsville on the historic Winters Lane that connects Route 40, Edmondson Avenue and Frederick Road.

Diggs would write a dozen more. “Surviving in America” told stories about neighborhoods in Oella and Granite and on Church Lane, Oakland Park Road and Winands Road in Randallstown. His last book, published in 2020, was “African Americans Laid to Rest in Baltimore County, Maryland.”

It was in the 1990s, while working as a substitute teacher at Catonsville High School, that Diggs decided to try his hand at history. He realized that many of the black students were not able to trace their ancestral roots. It became a labor of love.

Fred Diggs, the youngest son who is an engineer in Washington, said his father “took his retirement years and found a piece of history that wasn’t well documented and found history treasurer of African Americans in Baltimore County. “I’m very proud of him for that.”

Diggs’ literary process involved dogged research, interviewing eager as well as reluctant subjects at their kitchen or dining room tables, transcribing those interviews and notes, scanning old photos and putting pen to paper. He used a typewriter but also was an early user of Apple Macintosh computers. By the time he wrote his final chapter, Diggs had incorporated more than 3,000 pages, 6,000 images, and hundreds of oral and video history.

In addition to stories about everyday life, Diggs’ meticulous work helped refute stereotypes about blacks and their historical contributions to government, education and the military. He conducted lectures and workshops in genealogy research to local audiences, well into his eighties. During the pandemic he told stories virtually, apologizing at times for not remembering some of the details.

So notable was Diggs’ work, the late County Executive Kevin Kamenetz established an award in 2016 to recognize blacks making a difference in the county and named the award in Diggs’ honor.

When Baltimore County hosted various activities, Diggs usually was tapped to participate. At the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project lynching ceremony held in 2021 in Towson, Diggs unveiled the Equal Justice Initiative historic marker for a lynching victim, Howard Cooper. During a special observance at the site of what used to be Catonsville High School, Diggs helped uncover the drape of a civil rights marker recognizing a 1935 effort to desegregate Baltimore County public schools.

Speaker of the House Adrienne Jones was a friend and supporter of Diggs. Thanks to a state grant she secured, the former Cherry Hill African Union Methodist Protestant (AUMP) Church, built in 1887, was renovated and converted to the Diggs-Johnson Museum on African American History and Heritage. Diggs founded the museum with his friend and fellow history buff Lenwood Johnson, which opened in November 2015 in Granite. He gave talks there.

“He was thrilled,” recalled Jones, a member of the museum board and one-time recipient of the Diggs Award. “He was very engaged, particularly in letting young people and students know their history.”

Diggs also enjoyed educating people on the bus tours he hosted as part of the Baltimore County African American Cultural Festival.

Betty Stewart was a longtime friend and assisted Diggs on the tours and with research. She met Diggs when he underwent heart surgery at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “I was his nurse. We talked. We just clicked. I saw he had this book [“It All Happened on Winters Lane”] in his room, and he signed it for me,” says Stewart.

She later ran into Diggs at Security Square Mall where he had a display of photographs set up in the food court. (Attendees at his homegoing service held Nov. 15 at United Bethel AME Church in Randallstown had an opportunity to see the photos.) After that renewed acquaintance, the Windsor Mill resident began helping him with the bus tours and even documenting grave sites at Loudon Cemetery as research for his tenth book, “African Americans from Baltimore County Who Served in the Civil War: Maryland’s Six Regiments of Slaves.”

Stewart recalls, “To see him move from one headstone to the other, it was peaceful. He looked up everyone one, which regiment they were in,” recalls Stewart, who also received the Diggs Award. “He had a love and a passion for preserving the history of African Americans in Baltimore County through old photographs and tours.”

Born in Baltimore City, Diggs dropped out of Douglass High School to join an all-black Maryland National Guard unit. His unit was federalized and deployed to fight in the Korean War, becoming the first black company in Korea. Over the next two decades in the U.S. Army, he saw action in Korea and Germany. One of his most notable assignments was serving as Sergeant Major of the ROTC Detachment at then Morgan State College from 1957 to 1964. For the next four years he was assigned to West Germany and moved his family there. He returned to Catonsville and retired from the military in 1970. He took a position at a high school with Washington, D.C., Public Schools as a military instructor and later became an assistant administrator.

Later, in his 40s, Diggs finished his education. He got his high school diploma, and within the next six years earned an associate’s degree from Catonsville Community College, a bachelor’s degree from the University of Baltimore, and master’s degree of public administration, also from the University of Baltimore.

In addition to his son Fred, Diggs is survived by sons Blair Diggs, who serves on the museum board, Terrance Diggs, a sister Nettie Holley, 10 grandchildren, five great grandchildren, other relatives and friends. His eldest son Louis S. Diggs Jr. (“Bunky”) died in 2018. His first wife of 61 years, Shirley Washington, a library clerk who died in 2015. He later married former high school sweetheart Elizabeth Diggs who passed away in 2021.